A Vernacular of Inclusion

Extending our understanding of the basic forms that shape our built environment to our understanding of the policies and practices that shape our social, economic and political structures may enables us to see how power relationships between privileged and oppressed remain fundamentally constant. Because the underlying forms that protect access for a few and limit access for everyone else are redundant and mutually reinforcing, we need to develop clarity about where we are trying to go in principle. Can a “formal” understanding of economic, social and political structures help us develop a new “vernacular” that helps us work together even while we work separately?

What do we mean by “vernacular”?

In the context of language, a vernacular is the language spoken by ordinary people in a particular region or local. The term is used in the architectural context to refer to ordinary building methods and styles used by people to build ordinary buildings. In places where the vernacular is widely shared and understood, the resulting town or city has a sense of cohesiveness and clarity. For example, in San Francisco the vernacular architecture is that of the Victorians. In New York, you can experience vernacular architecture in the neighborhoods populated with brownstones. In both cases, there is a shared understanding about how buildings meet the sidewalk and the street, how building form is adapted to accommodate relatively public or relatively private uses, and how mid-block buildings meet the street in one configuration while corner buildings another. The lack of or presence of a level change at the entry, window size and placement, portions of the building overhanging the sidewalk, etc combine to communicate the building’s relative degree of public to private access. The individual building developers, owners, inhabitants, and visitors do not need to communicate with one another directly about a building’s public to private use, but rather share an understanding based on a shared building “vocabulary”. The end result in the built environment that is built based on a shared vernacular architecture is a shared sense of having arrived in a particular neighborhood or city.

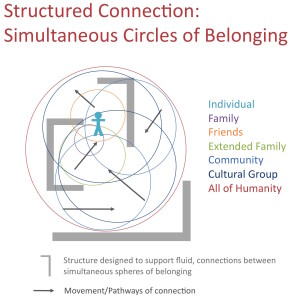

Just as it is desirable in the built environment to have varying degrees of enclosure and containment relative to the purpose of each setting, social boundaries can serve similar constructive purposes. For example, grouping all of humanity into one group in all circumstances could become unwieldy or uninformative; rather, recognizing that we choose to form sub-groupings such as families and cultural groupings, and that society puts us into different sub-groupings, is helpful in understanding how different people are situated relative to each other. Each of these sub-groupings does not inherently preclude our membership in other sub-groupings (past, present or future). Clearly, one can argue that these boundaries help us navigate complex social environments.

The degree of containment in a social environment, just as in the built environment, can be complete, partial or directional. Social norms and policies define who belongs and doesn’t belong to socially marginalized and social privileged groups, which in turn has cross-generational implications. For example, we can examine the evolution of who is and isn’t white. Those included in what we know today as “white” has fluctuated over time; some cultural groups were at some point excluded and were later included (e.g. Irish), some cultural groups have been legally admitted and dismissed, some divisions have become tighter with time, others more porous. Who is white is not genetic, nor is it cultural, but rather it is shaped by policies that determine who is included and served by society, and to what degree. In other words, who is inside and who is outside the circle of human concern has shifted over time, but the mechanisms used to build this sense of inside and outside share an underlying vocabulary of exclusion.

And just as buildings are remodeled and rebuilt to “modernize” and fit the present moment, so too have the boundaries of racialized groups. Society creates these boundaries and assigns meaning to them; depending on the assigned meaning, these boundaries are more or less porous, and have more or less tangible impacts – in other words, contain and enclose the members of a sub-grouping to different degrees and to different ends.

Containment & Enclosure

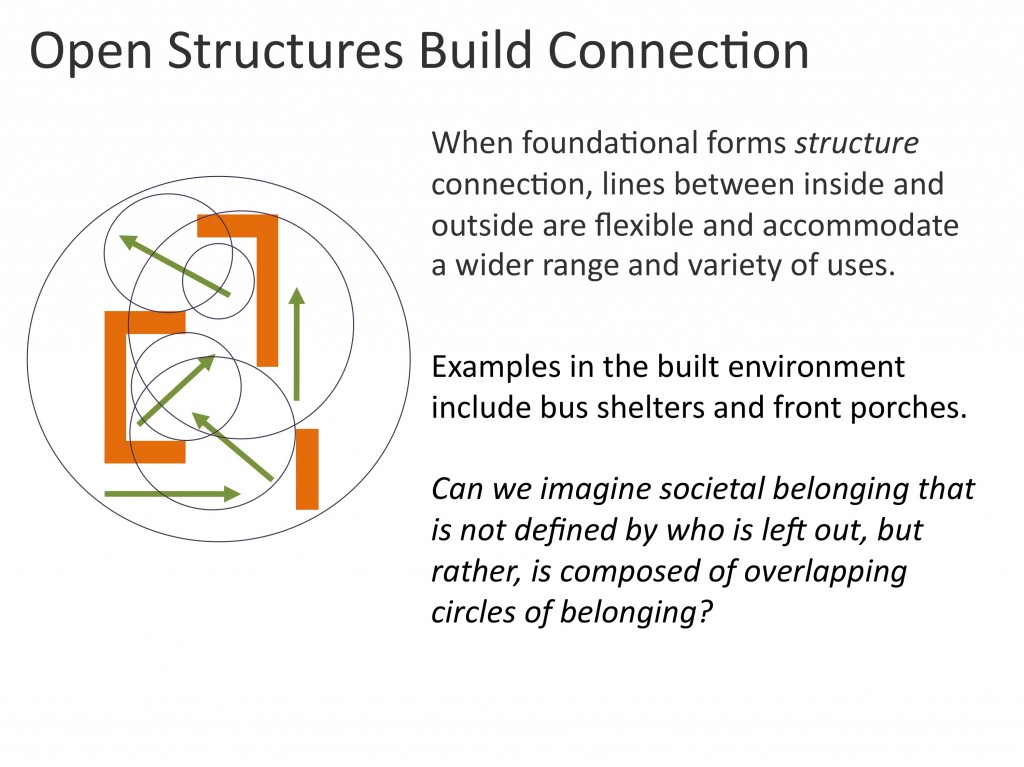

To understand the impact of our policy environment, it is necessary to evaluate the ways in which policies, cumulatively and reciprocally, create, reinforce, or interrupt the degree of containment and enclosure of different social groups. In other words, it is helpful to recognize the different types, forms and patterns of boundaries and how the choice of boundary mediates connection and separation.

Renee Chow describes containment in the physical environment as “how material elements hold and indicate spaces….containment can be complete, partial or directional” (Suburban Space: The Fabric of Dwelling, 2002. p. 73). For example, in a traditional building, the boundary of a room is clearly indicated by four walls that separate activities that take place inside the space from activities outside of that space. Connections to outside activities are limited to openings (doorways or windows); when the door is open, you can walk through or call out to someone in the adjacent space, when it is closed you cannot. By design, these openings are easily controlled.

If, on the other hand, we think of an urban front porch built with columns and a roof overhead, the form provides not only shelter, but also a transition between the street and the house. Columns, the most minimal variant of a wall that still provides structural support for a roof and partial delineation between inside and outside, maximizes connection and minimizes separation between public street and private house.

Conventional structures, the room and the porch, are so common to our lived experience that we rarely question their placement, their size, or more fundamentally, if they are creating the desired degree of separation or connection given the activities they are designed to support. In other words, the way in which a space is composed circumscribes and controls our experience of connection and separation.

Transform structure to change outcomes

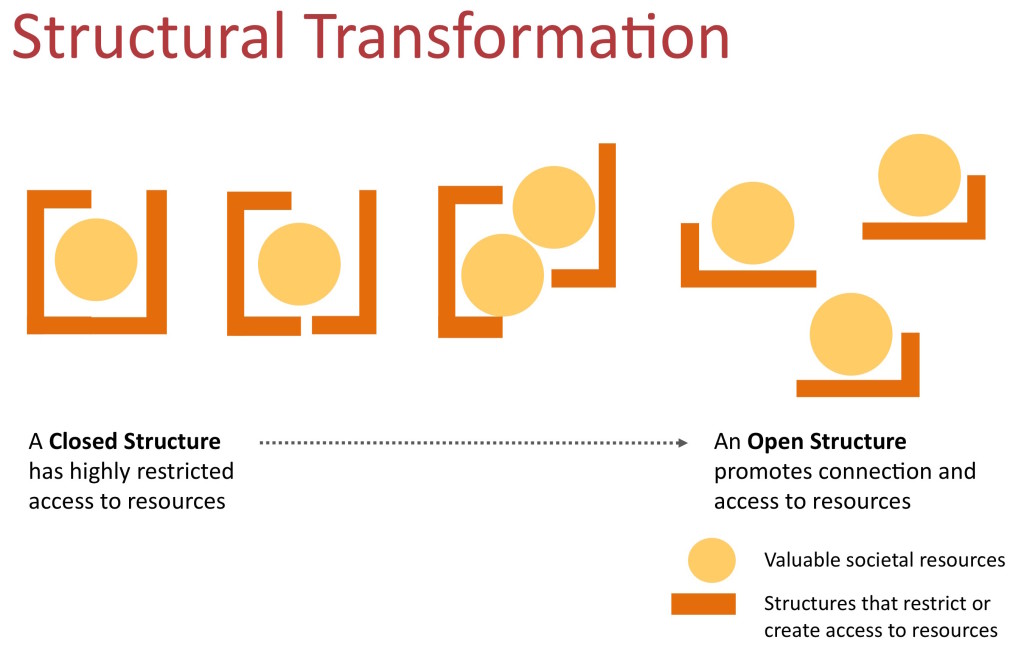

Similarly, in human social settings, containment is achieved through social norms that bound and separate. In social science this is often referred to as “othering”. The degree of othering, or containment, can be complete, partial or directional. For example, social norms define who belongs and who does not belong to a particular family, faith or racial group—who is included, who is not, and what the entry points are. Society constructs these boundaries and assigns meaning to them, and depending on the assigned meaning, these boundaries are more or less porous, have more or less tangible impacts. In other words, these boundaries contain and enclose the members of a sub-grouping to different degrees and to different ends or outcomes.

If we think about this in terms of the built environment, we might think of the work that a fence does to provide enclosure. In some places, a fence makes sense, for example at the perimeter of a school play yard; a clear boundary both gives children freedom to roam, and also protects them from roaming too far. However, when an environment becomes too full of fences, the inhabitants experience those fences as barriers or even as a cages, where enclosure becomes complete and is simply a devise to separate and obstruct access.

Just as it is desirable in the built environment to have a variety of degrees of enclosure and containment, and different degrees of containment are appropriate to different settings relative to the purpose of that setting, social boundaries can serve similar positive purposes. For example, grouping all of humanity into one group in all circumstance would become not only unwieldy or uninformative, it is helpful to recognize that we choose to form sub-groupings such as families and cultural groupings, and that society puts us into different sub-groupings. Recognizing human desire to create subgroups is helpful in understanding how different people are situated relative to each other. Each of these sub-groupings does not inherently preclude our membership in other sub-groupings (past, present or future). Clearly, one can argue that these boundaries have emerged not only to limit access, but also to help us navigate complex social environments.

Social Forms of Containment

In most traditional architecture, four walls or a continuous wall, define a space that is considered to be “inside”. It is the domain of family, rather than strangers, it is the safe space, rather than wild, uncontrolled natural or outdoor space. Access to the inside is limited and easily controlled and regulated both physically and by social custom.

What differentiates modern architectural space from traditional is the separation of the system used for load bearing structure from the systems used to provide spatial separation and connection.

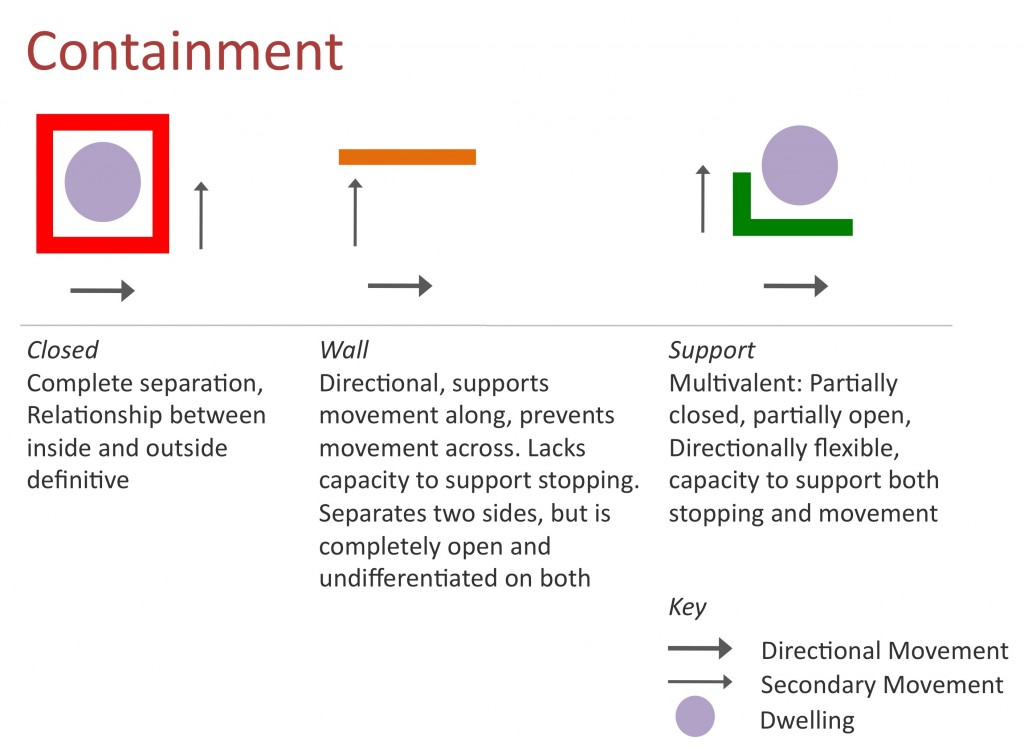

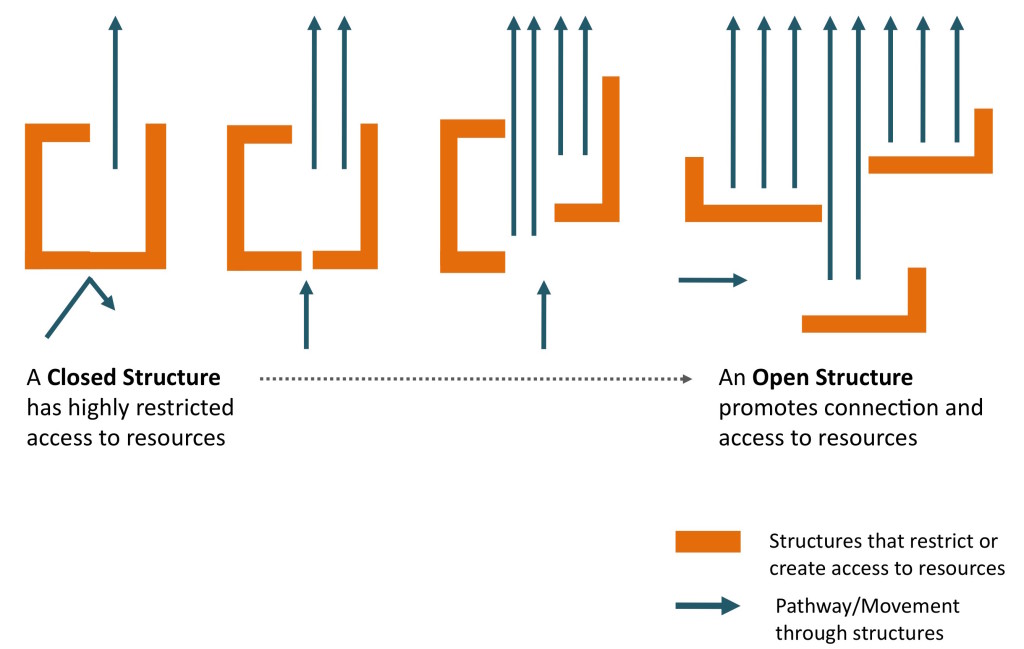

If wall placement is determined by the need to support the weight of the building, the building perimeter and the rooms it contains are set and are relatively inflexible. However, if wall placement is independent of load bearing, the definition of ‘a space’ or ‘a room’ becomes flexible, allowing the users to interpret and configure the space to fit their specific needs and desires. For example, if two three-sided spaces are oriented open towards each other, but shifted so that short walls do not align, at least seven spaces are created, each of which provide differing degrees of containment and enclosure, connection and separation. This is not to say that this configuration is optimal in all circumstances, but rather to demonstrate how a relatively small shift in structure can radically change the experience of separation and connection among adjacent spaces, creating a new and wider range of potential possibilities for how activities and the people participating in them relate to one another.

If we consider the policies in the United States impacting enslaved African Americans and their descendents, the 14th and then 15th Amendments to the Constitution were the equivalent of opening a window and a door into the walls of a completely contained room defined by four solid walls of separation between white and non-white. Despite the creation of openings, the fundamental form of the room was not changed—economic, social and political barriers remained intact—setting the formal guidelines for the creation of segregation and the present day racial contours of mass incarceration and detention.

The House of Jim Crow continues to be defined by four walls that are oriented relative to each other for the purpose of creating separation and containment. In order to open up opportunity and thereby create an equitable society, the underlying form and structure must be transformed and redesigned to remove the barriers that create and sustain separation. Just as buildings have adapted to evolving and changing needs, our political, economic and social structures need to adapt and evolve. And just as modern architecture has transformed how we think about how we define spaces and the relationships between them, we, too, must transform structures of societies to reflect our evolving understanding of interconnectedness and humanity.

What interventions, what transformations in policy and culture can we make to support and facilitate more porous, fluid connections between groups of people and the opportunities available to them?