Form (noun) 1a: the shape and structure of something as distinguished from its material1

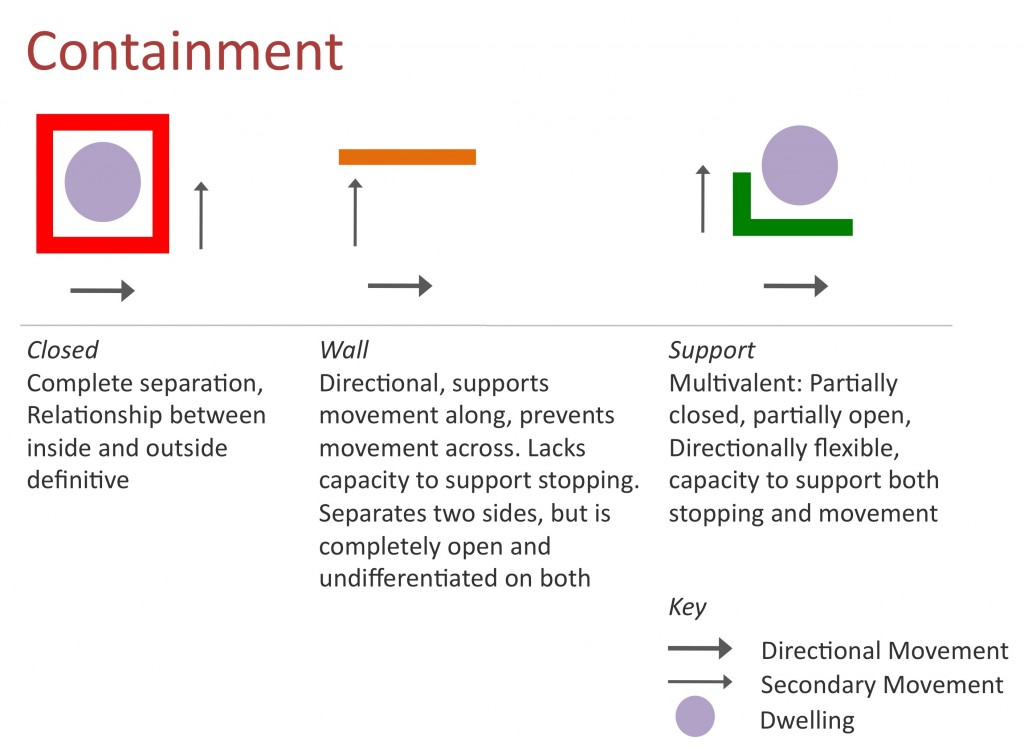

In this section, we explore basic forms and the work that they do. We begin by identifying form in its more concrete expression—form as experienced in the built, tactile environment. The three basic form types include: the box (or 2 ‘C’s), one wall (or ‘I’), and a wall with a short return (or ‘L’). Whether these walls are curved or not, makes little difference for our purposes; we are concerned with how different forms, in isolation and in relation, create separation and connection between spaces relative to movement and dwelling.

Two ‘C’s maximize containment and separation and prevents movement. The ‘I’, depending on its orientation, separates movement across or connects movement along its face, and the ‘L’ invites dwelling, reinforces movement along and supports movement across.

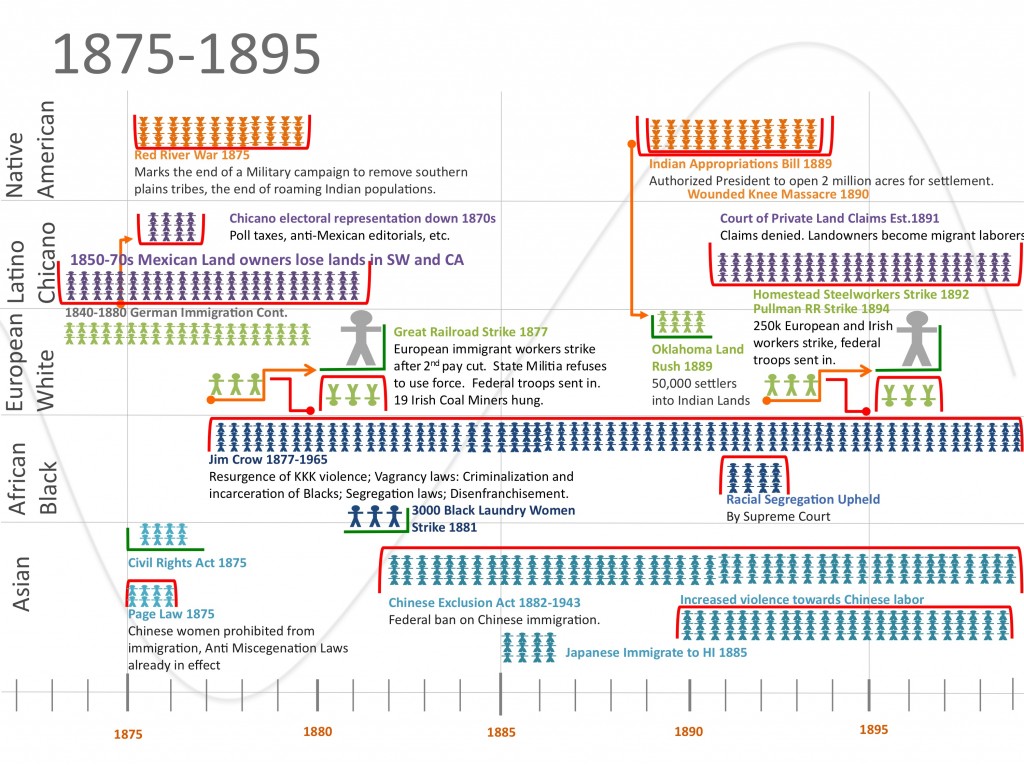

Using this tactile and experiential understanding of form and the relationship between access and form, we examine the ‘form’ of our policy environment relative to advancing equity and ending poverty.

Are there patterns and relationships between policies that cumulatively create, reinforce, or interrupt the degree of separation and connection between different groups of people and their relative access to meaningful, well paying work, affordable, high quality education, stable, secure housing, etc?

In the timeline above, the red ‘C’ form represents separation, the green ‘L’ form represents connection, multiple people represent human beings, and the large ‘person’ represents the Elite or corporations.

- Merriam Webster Dictionary online, accessed 10/16/2012

Experience & Form

Form in its most concrete expression is experienced as we move through and live in the built environment. Architect Renee Chow describes containment in the physical environment as “how material elements hold and indicate spaces. . . . [and that] containment can be complete, partial or directional”1. The basic form categories described below are found in our environment in a full range of scales—from a phone booth that can accommodate one person, to a room that can hold 50 people, to a fortress that can accommodate thousands.

The Box

In a conventional building, the boundary of a room is clearly indicated by four walls which separate inside from outside. Connection to the outside is limited by openings that are easily controlled and are created by removing part of a wall. Experiences inside are distinct and separate from experiences outside the space. The box creates complete containment and maximum separation whether at the scale of the phone booth, a jail cell, a gated community, or a national border. The placement of the perimeter determines who or what is considered to be inside.

The “L”

On the other hand, whether at the scale of a residence or a state house, an ‘L’ form, provides provides a degree of separation from the outside and an equivalent degree of connection to the inside. Partial shelter of a porch creates a transition zone between the minimal containment of the street and the more complete containment of the building. Public access to and from the front porch, whether the building serves a public or private purpose, has a lower level of control by design and intention relative to the interior, and a higher level of control relative to the street. The form of the ‘L’ provides partial containment and suggests connection whether we think of a covered bus shelter, a covered sidewalk, a state house or a shipping port.

The Wall

Finally, consider the form of a wall. In the built environment, a wall provides separation and enclosure. In some places, a wall makes sense, for example at the perimeter of a school play yard; a clear boundary both gives children freedom to roam, and also protects them from roaming too far. However, when an environment becomes too full of walls, barricades and fences, the inhabitants experience those walls as barriers or even as cages where enclosure becomes complete and serves to separate and obstruct access or movement. The wall provides containment or connection depending on the direction one is approaching that wall and the direction one hopes to go.

Form constrains or connects

The physical form of the environment by design, constrains to a degree, the inhabitant’s relationship to adjacent spaces. The space created by four walls of a room is definitively bounded, clearly separating ‘inside’ from ‘outside’.

A freestanding wall, oriented perpendicularly to movement, creates separation, even if ultimately permeable. The 8 Mile Wall in Detroit separates two economically and racially divergent neighborhoods and the Berlin Wall and the wall along the US-Mexico Border separate countries.

On the other hand, a freestanding wall oriented parallel to movement reinforces that movement. The walls formed by the aisles of a grocery store encourage people to move back and forth the full length of the aisles, adjacent buildings along an urban street together reinforce movement along the sidewalk.

The “L” shape of the bus shelter separates while it also connects by offering both a place to stop while simultaneously maintaining a visual connection between those who have stopped and those who move past. The form of the ‘L’ supports a wider range of activities and has more “capacity” because it allows inhabitants to choose his or her relationship to the form depending on immediate need. A pedestrian can stop and wait for the bus or hide from the rain under the bus shelter, or she can choose to continue walking along the sidewalk to her destination.

While architectural forms are not deterministic, the configuration of walls and openings, their scale, their capacity to accommodate dwelling and their relationship to each other—how they are oriented to one another relative to movement—shapes one’s experience of the space.

As the removal of the Berlin Wall demonstrates, though built forms may appear permanent and unchanging, as political priorities change, forms change. And just as historic buildings and barriers continue to shape our cities, our inherited policy landscape leaves residual impacts that need to be recognized and addressed in subsequent designs, whether one is a designer of buildings, cities or policies.

- Chow, Renee, Suburban Space: The Fabric of Dwelling, University of California Press, 2002, 1st edition, p. 73.

Intentionality & Form

Coming soon