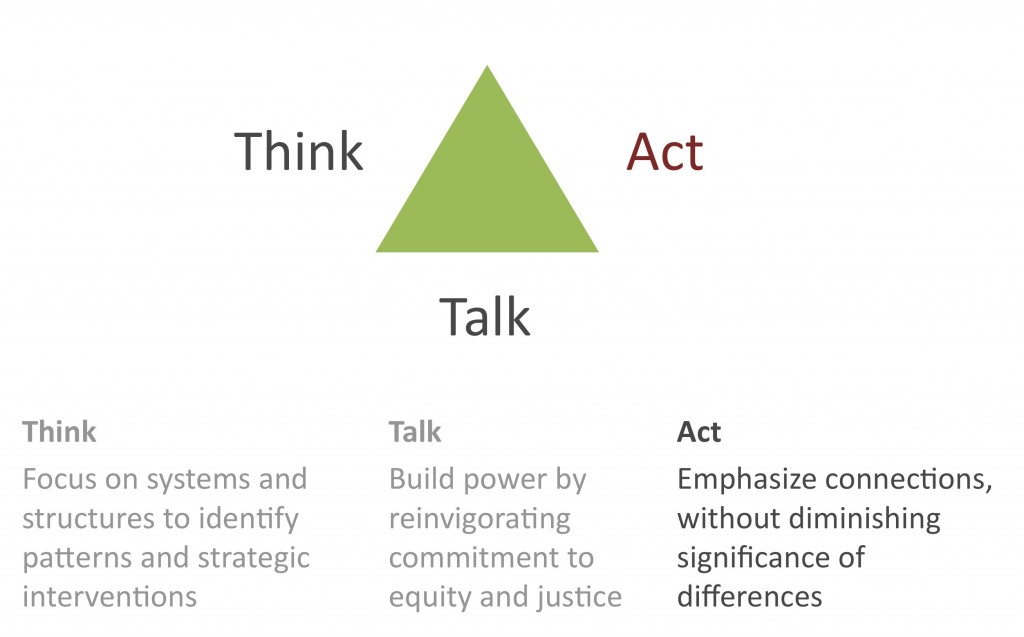

To understand Power, we begin by looking at how different groups are situated relative to each other and to power. What does this suggest for strategies for how we organize, how we structure our organizations and what approaches we take to build collective power for transformational structural change? After looking at different kinds of power available to us for making change, we examine the range ways that we might define our problem and subsequently, the range of interventions we might make to address these challenges. Finally, we explore the concept of ‘targeted universalism’ as an organizing tool, an approach to policy making that addresses our relative situatedness, and as a framework for communicating universal goals informed by the significance of our differences, to strengthen both our articulation and commitment to a shared goal.

Situatedness

Are We All Equally Situated?

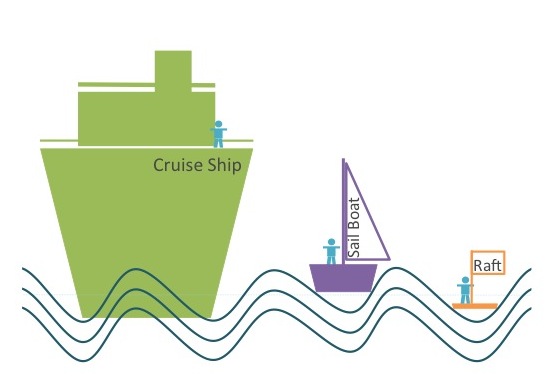

A big storm is coming in. Three people are out to sea. One person is on a large cruise ship, one is in a sailboat, and one is in a makeshift raft. To treat everyone equally, your plan is to pick everyone up in six hours. Will your plan work equally well for everyone? What would be a better plan?

We come from different places—different neighborhoods, countries, cultural backgrounds, class backgrounds, educational backgrounds, and so forth. As a result, we are all situated differently. As such, we bring different knowledge, perspectives, kinds of leadership and access to power—all of which are needed to build collective power. Unfortunately, these differences often bring attendant intergroup tensions.

In traditional approaches to building power, organizers look for existing common interest. This builds transactional power, or power based on a time-limited exchange that leaves the underlying structure and associated tensions intact. If, on the other hand, we recognize the different ways that we are situated within a structure and reveal the multiple ways the problem is created and re-created, we can respond with interventions that transform the structure itself. This builds transformative power.

To build transformative power, we need to reveal that our interests are “situational” (i.e., related to our situatedness) and accordingly not all tensions are personal. Through inclusive processes designed to identify structural tensions, we can build trust and shift our focus onto underlying structures. Often this reveals the need to change the structure of our own institutions so that they transform our relative situatedness. To influence and direct decisions that impact our lives will require institutions that have the capacity to support inclusive, long-term collaboration with a wide range of organizations, some of which have similar capacities and others that have very different capacities.

While personal and social responsibility are important, and should remain in our advocacy and analysis, our approaches need to consider the structures and systems that are creating and perpetuating disparities. By doing so, we can challenge policies, processes and assumptions to create lasting change. Transformative thinking leads to transformative power.

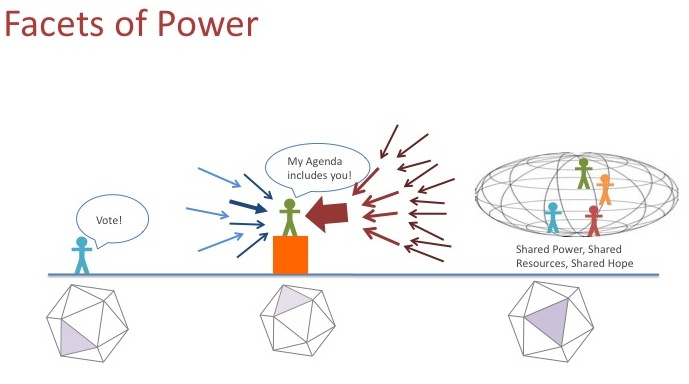

Facets of Power

Power has many facets, or different ways of exerting itself, in the political, economic, and social conversations of human societies. Grassroots Policy Project’s paper, The 3 Faces of Power1, outlines three critical ways that people exert power to shape outcomes: direct political involvement, building infrastructure to shape political agendas, and shifting worldview.

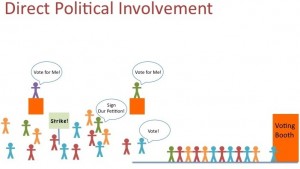

Direct Political Involvement includes activities such as trying to win issue-based campaigns, helping candidates get elected to public office, taking legal action, and engaging in direct action to change laws and policies, and impact decisions effecting our lives.

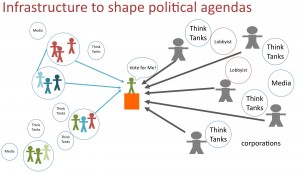

Building Infrastructure includes activities that build sustained membership involvement and relationships with other types of organizations, support collective action, develop leaders for a wide range of organizations (think tanks, advocacy groups, etc) and coalitions, identify and develop candidates for public office, build and maintain coalitions, alliances and collaborations, and expand political agendas to unite different constituencies and issues to shape the political agenda.

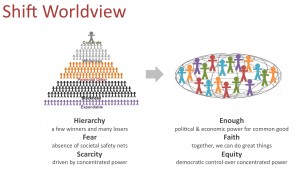

Shifting Worldview includes engaging in activities to shape ideas and the way people make sense of what they see and hear, link short-term work to long-term goals and to a broader vision, challenge current dominant worldview, and frame issues with common, values based progressive themes that reinforce an alternative worldview and expand what seems possible.

The Work of Structures

When we participate in any of the three faces of power above, it is essential that we recognize and address the hidden power that structures exert to shape worldview and discourse. Built over time through policies, practices and social norms, structural marginalization, whether racial, gendered, or class based, or any other systematic marginalization of entire groups of people, creates disparate outcomes that social norms and popular discourse willingly attribute to bigoted individuals or isolated exclusionary institutions, rather than acknowledge and proactively address.

As the title of Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s book, Racism without Racists2 neatly summarizes, the power of structures is the ability to shape and determine outcomes for groups of people without the presence of individuals whose actions are motivated by personal animus. This raises the importance of a) recognizing the expressions of structures designed to create inequity and b) the imperative to design new structures to create equity with intention and, c) the necessity of developing mechanisms to access whether or not the new structures create opportunity and equity.

- http://www.strategicpractice.org/system/files/three_faces_of_power3.pdf

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo, (2003) Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America

Strategies for Intervention

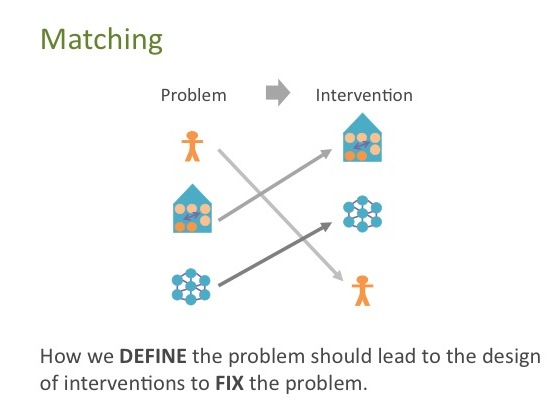

How we define a problem informs how we try to fix that problem. For example, we observe that the bird inside the cage is not well. Is the bird sick? Is the birdcage open, but the bird does not fly out because it can’t find the opening? Is the opening is too small? Or do caged birds need to be freed?

The action we choose to take or intervention we choose to make should be based on our assessment of what we think will fix the problem. In the case of working towards racial equity, it is helpful to remember that the problem of racialization and accompanying inequity occurs in at least three different levels: Interpersonal, Institutional and Structural. Using this three-part rubric can be helpful in checking that your problem and the proposed solution are appropriately matched.

- Brainstorm a list of the problems your community faces

- Sort the problems according to the level of change that it requires. To fix the problem, will you need to change Individual behavior? Change Institutional practices? And/or change underlying Structural relationships?

- Brainstorm a list of possible interventions to fix each of these problems. It will likely be more difficult to think of interventions to fix institutional and structural problems than to think of strategies to change or develop individuals.

- Sort the interventions according to the level of change that it will make. Will the intervention change Individual behavior? Change Institutional practices that impact different populations differently? And/or change policies or inherited historical relationships that result embedded Structural inequities?

- Do any of the interventions have the potential or more promise for addressing problems at a different level of change or have impact in another issue area as well? How many people is the change likely to impact? What is the likely time frame for making that change? Will it lead to other positive changes?

- What kinds of interventions in the other levels will you need in order to achieve your desired outcomes? For example, will you need leadership development in order to have leaders in a collective effort to make structural change? Will you need a vision of structural change to inspire leadership amongst institutions and individuals in your community?

- Is there a sequence in which policies need to be changed?

Targeted Universalism

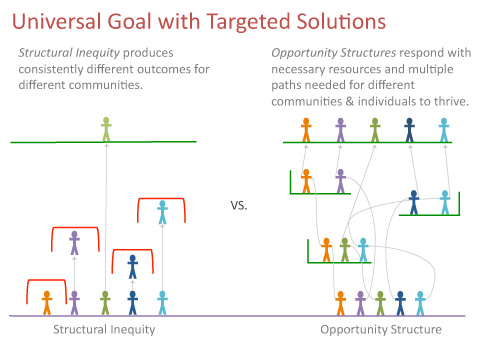

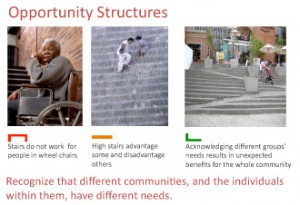

Typically, policies are designed to be “universal” and apply equally to all individuals, based on an assumption that all individuals will receive equal benefit. In other words, universal policies assume that if you provide a stairway everyone will be able to make it to the top. For example, school funding: the assumption is that if all children have the opportunity to go to school, each child will have an equal chance to obtain higher education.

However, Systems Thinking and Structural Racialization analysis shows that communities are situated differently relative to each other due to many factors, including history, education, language, and access to community assets.  In other words, a stair way does not provide equal or equivalent access to a person who uses a wheel chair, a stroller, or has difficulty walking up stairs. In practice, universal policies create differential access to opportunity.

In other words, a stair way does not provide equal or equivalent access to a person who uses a wheel chair, a stroller, or has difficulty walking up stairs. In practice, universal policies create differential access to opportunity.

Targeted Universalism is a frame for designing policy that acknowledges our common goals, while also addressing the sharp contrasts in access to opportunity between differently situated sub-groups; barriers to quality education, well paying work, fair mortgages, and so forth. To transform structural inequity into structural opportunity, policies need to address these contrasts and measure success based on outcomes.

For example, school assignment policies can be created using indicators such as educational attainment and median household income of neighborhoods to draw attendance zones and boundaries, thus increasing pathways to opportunities for neighborhoods that would otherwise be isolated. Voluntary school integration plans using multiple indicators have been successfully implemented in Jefferson County, KY; Berkeley, CA; Montclair, NJ; and Chicago, IL. Where school assignment policies are insufficient, resource allocation strategies can be designed so that schools have access to the resources students need to thrive.

Rather than maintaining structures that separate people from societal resources, or limit access to those resources, we need to redesign our structures to build opportunity and to connect people to the supports that they need to thrive. By considering the challenges that different groups face, we are able to build healthier structures. Healthier, stronger structures bring benefit to all groups. How structures are built matters. And if we want different outcomes, we need different structures and different relationships between structures.