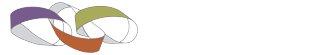

To understand Systems Thinking, we focus on how issues and problems are interconnected and offer tools to help identify strategic points of intervention that also build possibilities for collaboration across difference. In this section, we delve into the concepts of Systems Thinking, Structural Inequality, Structural Racialization, and Opportunity Structures.

Structural Inequality

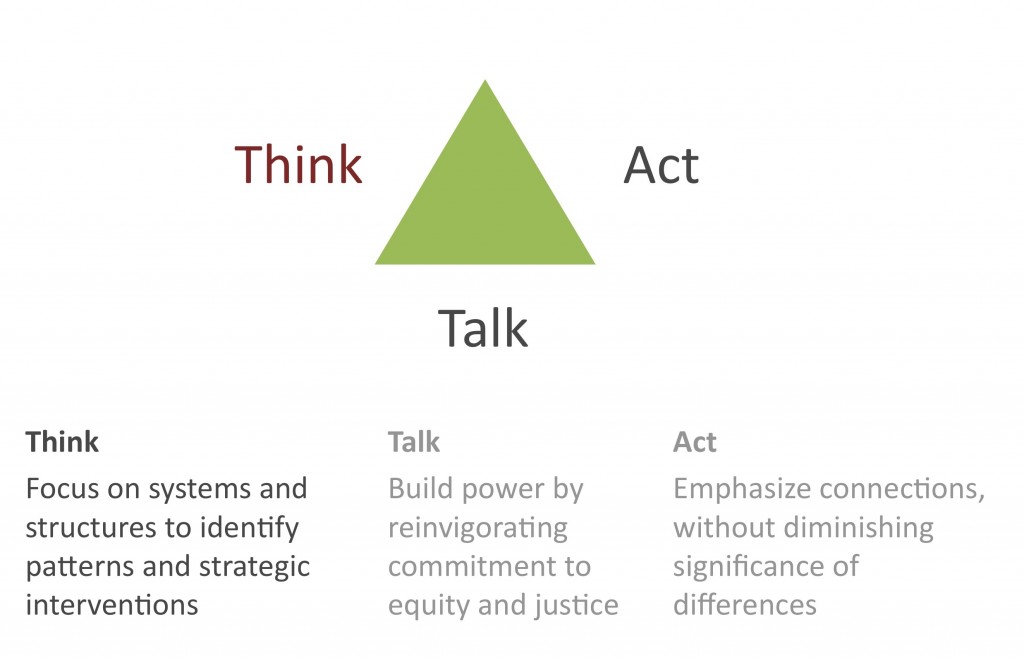

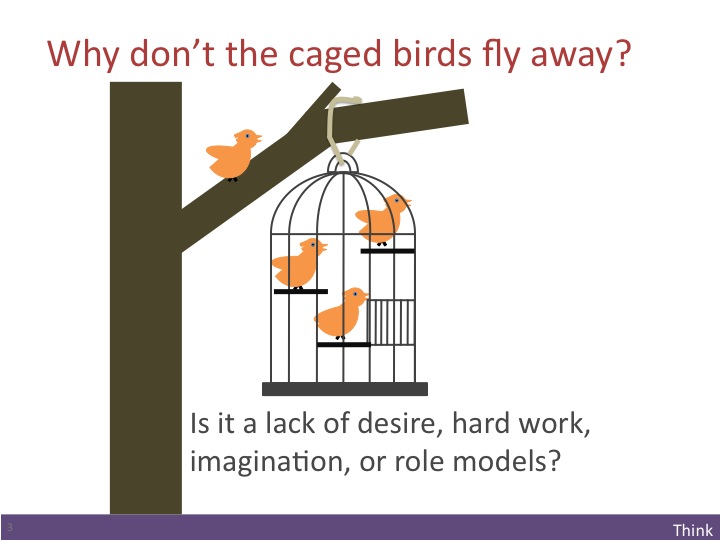

Why don’t caged birds fly away? Is it a lack of desire or imagination? An unwillingness to work hard or a lack of positive role models? Is it because caged birds are somehow biologically unable to fly? Of course not! Caged birds cannot fly because they are locked inside a cage: a cage that has been built to be virtually impossible to escape. In fact, when a caged bird escapes, the owner or the person who put them in that cage in the first place, goes to great effort to return the “escaped” bird to the cage.

We cannot explain why the bird cannot fly away by looking at one bar of the cage. However, on evaluating the multiple bars arranged in specific ways that reinforce each other, we see that the effect of the bars is structural and cumulative such that the bird is trapped. Societal institutions also behave as cumulative structures, such that individuals face multiple barriers to changing their circumstances, even when they recognize what is wrong.

The outcome of structural racialization is a highly uneven geography of opportunity that constantly evolves, and, importantly, does not require explicitly racist actors to maintain. Societal institutions and relationships between those institutions give or take away opportunity for groups of people. These relationships create predictable outcomes for different social groups.

Structural inequity describes a dynamic process that generates differential outcomes based on class, race, gender, immigration status, history of incarceration, etc. While structural inequities appear to work well for some people, inequity in fact works against most people—even those who appear to be benefitting.

When a society is entrenched with structural inequity and inhibits mechanism to address persistent inequity, social supports for all members of that society are compromised by the collective commitment to insure that some members do not have access.

If we want different outcomes, we need to transform structures. If the caged bird cannot thrive, a systems thinking doctor would examine the cage and redesign the structure so that the bird’s needs are met rather than limited. Limiting our interventions on an issue to one individual, institution, or societal institution inherently limits our impact since it is the interaction of multiple institutions that creates enduring inequitable outcomes.

Our challenge is to recognize the processes that create predictable inequity, imagine alternative structural arrangements that would produce equity, interrupt the processes that currently create inequity, and build collective power to make those changes.

Structural Racialization

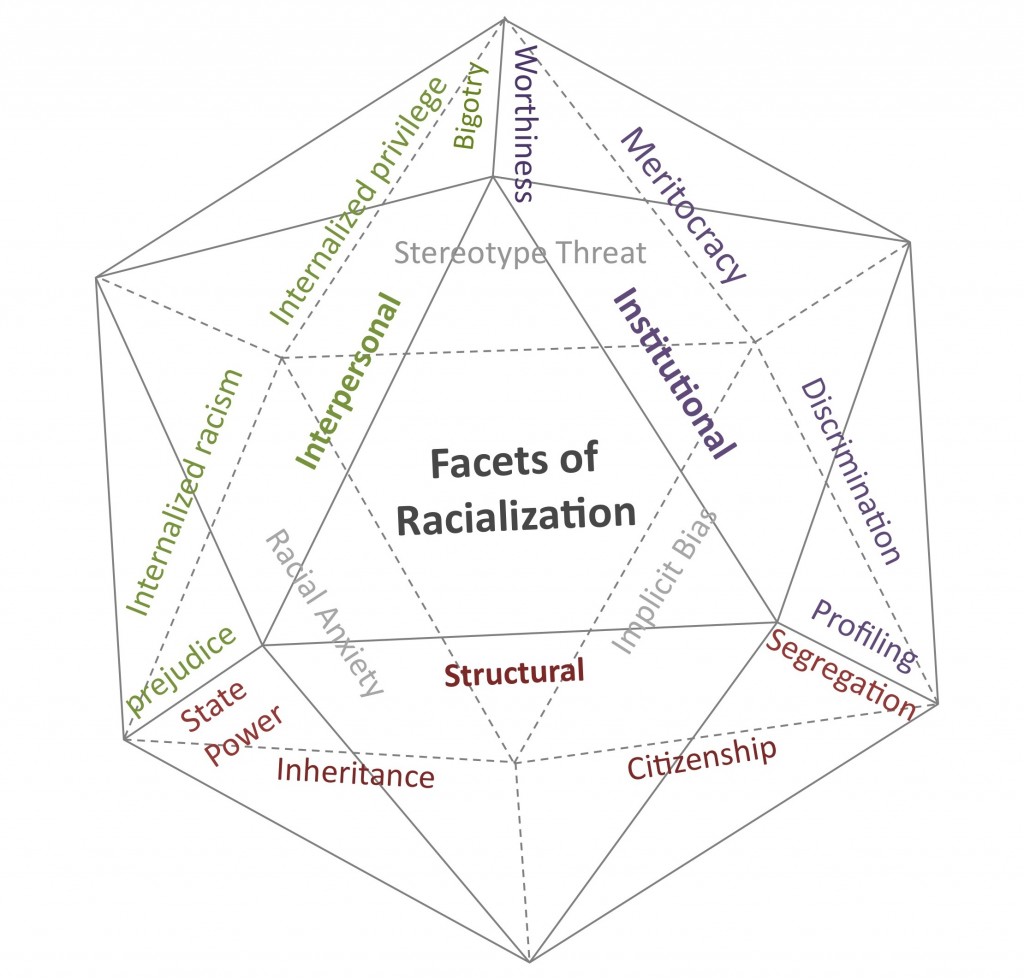

Race is multifaceted – shining light helps to reveal its complexity. While the concept of race is a social-political construct, meaning that the idea of race has been built over time, and it has no legitimate biological bases, the assignment of value and meaning to race has concrete ramifications on our lives.

Race is one way that our society sorts communities and people to allocate resources and access to those resources. In the United States, the maintenance of racial hierarchy creates, recreates, and obscures shared interest necessary to achieve equitable political, economic and social outcomes. We are taught not to see how race is used to undermine building and investing in shared institutions, and at the same time, to reinforce coercive power for the corporate elite.

Because race manifests itself simultaneously in multiple spheres of our lives, it is helpful to begin by thinking of three domains that shape our experiences: individual, institutional, and structural.

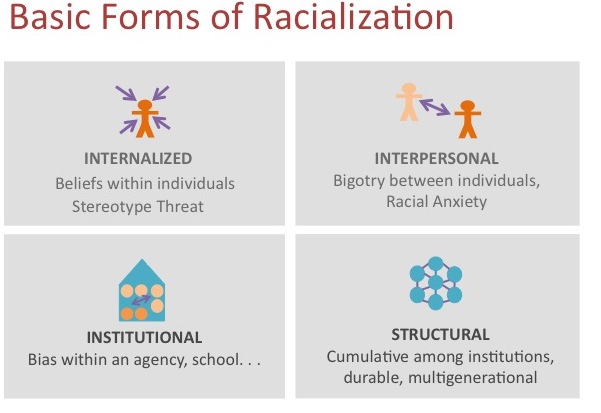

At the individual level, internalized racism and internalized white supremacy describes the conscious and unconscious beliefs we have inside ourselves about ourselves associated with our membership in a particular racial group. These shape how we interact with the world, how we interpret our experiences, and how well we perform in different contexts. Interpersonal racism describes racism between two or more people. The harshest, most obvious form of interpersonal racism is bigotry.

Institutional racism describes the behaviors, practices and policies inside an institution that create racialized outcomes. This is a very broad category in that an institution can describe a particular school, a school district, or an educational system.

Structural racism describes how the different facets of racism work interactively to reinforce a system of racialized outcomes that are considered “normal”, “natural” and “inevitable”. Structural racism does not require racist actors or racist intentions to produce racialized outcomes. Interactions between individuals are simultaneously shaped by all of these domains.

For the purposes of this discussion, we’ll focus on structural racialization. We use the term racialization to denote the dynamic process that creates cumulative and durable inequalities based on race. Structural Racialization often determines an individual’s or a group’s position in physical, social, and cultural opportunity structures – where a person lives, who they know, and what is considered normal. The outcome of Structural Racialization is a highly uneven geography of opportunity that constantly evolves, and does not require explicitly racist actors to maintain. Our challenge is to identify the most effective ways to interrupt the processes that create inequity.

Structural Inequality is the dynamic process that creates cumulative and durable inequalities correlated with race, gender, class, orientation, immigration history, incarceration history, etc.

A structural analysis examines how historical legacies, individuals, institutions and structures work interactively to distribute advantages and disadvantages along racial lines[i].

The home mortgage market provides one example of how government, banking, and real estate worked together in the post-war period, while Jim Crow was still firmly entrenched, to create a highly racialized landscape that continues to create racialized outcomes today, not just in home ownership, but across multiple domains.

Systems Thinking

Systems Thinking explores how institutions that effect opportunity are arranged, and to what result. In other words, by examining the structures that give or take opportunity from particular groups of people, the timing of the interactions, and the relationships that exist between them, we will have a more complete understanding of why certain outcomes persist. For example, it is helpful to reveal how health outcomes of a community are not simply a result of individual choices, but rather, are a function of opportunities, access to work, access to quality education, availability of high quality and affordable housing, and reliable transportation.

Typically, organizations focus on a single-issue or on a narrow set of closely related issues. We work on housing, or air quality or health, in communities that are defined by immigration, race, and class. By focusing on one issue, we try to explain differential outcomes for entire segments of the population, such as what groups of people live in substandard housing, breathe contaminated air, or have poor health outcomes. This approach uses a ‘one dimensional‘ understanding of an issue. Since our lives and issues impacting them are multi-dimensional, we need to use multi-dimensional thinking to understand differential outcomes and to strategize ways to achieve better outcomes.

In a Systems Thinking worldview, A is connected to B, C, D and E in such a way that causation is reciprocal, mutual and cumulative.

If we think about issues in isolation, we would consider A separately from B, for example housing separately from air quality, thinking that once we fix A, we can direct our energies towards fixing B. In practice, this often results in one group working on issue A and another working on issue B, and not working together even though A and B are linked.

With multi-dimensional thinking, or, ‘Systems Thinking,’ we can understand the context that produces consistently different housing, air quality, health, economic, and educational outcomes in different communities, strategize on multiple fronts, and open up the possibility of building greater collective power to change these outcomes.

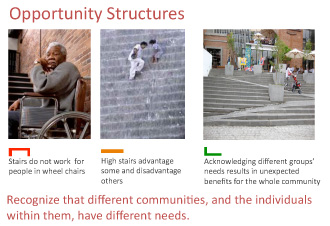

Opportunity Structures

Opportunity structures are factors that mediate our access to opportunity; they can be physical, social, or cultural, such as stable housing, healthy and safe environments, high quality education, sustainable employment, political empowerment, and positive social networks1. Opportunity structures are critical to opening pathways to success. In order to address structural inequities, including racial inequities, we must build robust opportunity structures.

Physical opportunity structures, such as commercial districts offering well paying jobs, quality schools, parks and green spaces, and distance from industrial areas, can be mapped to show how opportunity segregates along regional, racial and social lines. Opportunity Maps show the durable effects of redlining, and other historical forces that have determined which groups of people occupy what spaces2. For example, a comparison of the maps developed for the home mortgage industry in the 1930s, before the official end of legalized racial segregation, with current maps of demographic distribution and regional access to opportunity structures shows that racial segregation of communities persists along historical boundaries as does lower concentrations of physical opportunity structures.

Social opportunity structures include social connections: our network of social relationships and the resources they connect our communities to, such as jobs, credit, legislative action, etc. With the persistence of housing segregation and school assignment based on location of housing within a city or region, social networks and thus social opportunity structures remain insular.

Consider prison guards, a highly organized group with access to capital and legislative pull: they are able to make collective demands on institutions. Formerly incarcerated people, though a larger group, are situated differently with regards to social opportunity structures and have less access to collective influence. Some groups may be considered “invisible” in a community, such as the working poor, and other groups may be organized, but keep their efforts internal, such as some ethnic associations of recent immigrants.

Cultural opportunity structures are shared norms, values, and goals that are reinforced within groups. For example, in groups living in areas with few opportunity structures, attending institutions of higher education may be rare – this may be both an issue of access, the effect of physical and social opportunity structures, and reinforced by cultural norms, such as the expectation that young people may not graduate high school.

- powell, j. (2010) Regionalism and race. Retrieved from http://www.urbanhabitat.org/20years/powell

- powell, j. a. (2008) “Race, Place, and Opportunity.” Retrieved from www.kirwaninstitute.org/publicationspresentations/presentations/2010.php

Glossary

Implicit or Unconscious Bias occurs when a person’s actions or decisions are at odds with their intentions.

Opportunity Structures are social, physical and cultural components that shape outcomes and behaviors and help individuals and communities lead fulfilling lives.

Racial Schemas are the racial categories into which we map individual human beings. Implicit and explicit racial meanings associated with that category are then triggered when we interact with that individual.

Racialized describes persons, outcomes or results that are defined by race.

Racism is a social-political construct used to group people and differentially allocate resources of society based on that grouping. It is helpful to think about racism as manifesting in four ways: Internalized racism which includes beliefs within individuals, Interpersonal racism which includes bigotry between individuals, Institutional racism which includes bias within an agency, school, etc., and Structural racism which is cumulative among institutions, and throughout society.

Racist actor describes an individual with malicious bigoted intent.

Situatedness describes resources (opportunity structures) available to individuals or groups relative to other individuals or groups in society.

Structural inequity describes a dynamic process that generates differential outcomes based on class, race, gender, immigration status, etc.

Structural Racialization describes the dynamic process that creates cumulative and durable inequalities correlated with race.

Structural Transformation describes transforming the structure that creates and perpetuates disparities.

Systems Thinking is a way of examining social outcomes that takes into account the cumulative effects of seemingly independent factors.

Targeted Universalism is a frame for designing policy that acknowledges our common goals, while also addressing the sharp contrasts in opportunity between differently situated sub-groups.

Transformative Power is power used to transform the structure itself (as compared to transactional power which used to get something out of the existing structure).